This blog post presents a brief explanation of artificial neural networks and how they are used for prediction. It presents the material in two ways: first, in plain language without any mathematics; second, in simple language but with some mathematical notation.

High-Level Overview (no math)

A neural network is a computing system that is used to model a function that maps a set of inputs to their corresponding outputs. Inputs could be, for instance, peoples’ browsing history on an e-commerce platform, and the outputs could be the probability that each person would click on an advertisement. Or, inputs could be a set of images of animals, and their corresponding outputs could be the answer to the question, “is this image a cat?”

A neural network that has been presented with a lot of examples of such inputs will become quite good at recognizing the patterns and get a sense of how inputs relate to outputs. The network can process an input - a list of products a person has viewed online, or an image of an animal - that it has not seen before and, based on what it learned, correctly determine how likely the person would click on an advertisement, or whether an image is of a feline.

The neural network model is a collection of inter-connected nodes, or neurons, arranged in layers. The first layer is an input layer, which yields a mathematical representation of input of the function. The final layer is an output layer, which yields the output of the neural network, or its prediction. Between the first and final layers are usually at least one “hidden layer”, or layers of interconnected neurons. The image below presents an example of a neural network with two hidden layers.

![Figure 1: A scatterplot of Pearson’s father-son pairs, obtained from [3].](../../nnets/figure-1-cat.png)

How neural networks process information

Each individual neuron in a neural network functions as a decision-maker: it reads in bits of information, weights and sums the bits of information, and then outputs a decision. By arranging several neurons into a layer, we can make decisions from multiple inputs. With each layer, the network can make more complicated decisions - decisions that are based on input from the previous layer. That is why neural networks are often designed with several hidden layers - to be able to estimate very complex relationships between input and output. Returning to the cat-recognition example, one can imagine each neuron in the hidden layer of the above figure making a decision on the input. The first hidden layer’s neurons could ask “does the image depict a tail?” or “does the animal in the image have a face?”. In the second hidden layer, the questions could be more detailed, such as, “if the animal has a face, does the face have two eyes and a nose and whiskers?”

A neural network learns by seeing a lot of examples for which we have a desired output. For each example it sees, a network can adjust its decision-making mechanisms. Technically, this means adjusting its neurons’ weights, which represent how much value a neuron given to each input, and its neurons’ biases, which represent by how much individual neurons shift their decisions. The final weights and biases in a network are those that make the total difference between the output of the neural network and the desired output as small as possible. With each example, the network makes an adjustment of its weights and biases. Once the network is trained with a very large number of examples, it can make good predictions for unseen examples.

So, how exactly do we train a neural network to learn the relationship between input and output ?

How we can train a neural network

When we feed an input into the neural network, we want the network’s output of the neural network to be as close as possible to the desired output - the “ground truth” output associated with the input. So, we can start by expressing the difference between the network’s output and the desired output as a cost function. Then, we can use standard optimization techniques to find the set of weights and biases of the network that minimize the cost function.

Gradient Descent

A standard way of minimizing a cost function is with gradient descent - we start at a random feasible point and iteratively move in the direction where we decrease the cost function fastest, until we (hopefully) reach a minimum. For neural networks, this means shifting the weights and biases of each neuron in the network, such that the network as a whole has minimal cost.

In order to do this, however, we need to be able to determine in what direction to move - this means computing how the cost function changes with respect to all the weights and biases in a network. For large networks, this task is quite challenging! Hence, we use the backpropagation algorithm: a method for computing the change in a neural network’s cost function with respect to each weight and bias in the neuron.

Backpropagation

The backpropagation algorithm is a method for computing the gradient of the cost function. The gradient can be thought of as a function of how the cost changes when we make a change to a weight or bias in the neural network. By knowing the gradient, we can determine how to callibrate the neural network to decrease the overall cost.

Starting with the output layer, we iteratively compute how much the cost will change when we change a weight or bias in the neurons of that layer. After completing this computation for the output layer and the hidden layers, we get the gradient of the cost function. Typically, backpropagation is combined with gradient descent. As we compute the rate of change of the cost function with respect to the weights and biases of each layer, we can update each layer’s weights and biases according to the gradient descent rule. When the training terminates, we have (hopefully) found the set of optimal weights and biases that minimizes the cost.

Backpropagation is done in the following steps:

Input: Feed an example into the first layer of the network.

Feed Forward: Compute the output of each hidden layer. The output of a layer is the set of decisions made by each of its neurons. The “decision” of a neuron is a function of its weighted sum of the input from the previous layer. The output of each layer becomes the input of the next layer. After moving through all the hidden layers, compute the output of the output layer - this is the prediction of the neural network for that example.

Compute the error of the network: Here, “error” is a measure of how the cost function will change with respect to the values that it takes as input - the output of the final hidden layer. Specifically, the error is the gradient of the cost function with respect to the outputs of the last hidden layer, multiplied by the gradient of the outputs of the last hidden layer. This measures how sensitive the neural network’s output is when a change is made to the final hidden layer. When we know this, we can adapt the factors that contribute to a layer’s decisions (weights and biases) to reduce the error in the network.

Back-propagate the error: After computing the error of the final layer, we can repeat the step for each of the previous layer, moving from output layer to input layer. For each layer, we compute how the cost function will change with respect to changes in the output of that layer.

Output: Once we do this for all layers, we get the gradient of the cost function with respect to the weights and biases of the neural network.

Once we have computed the gradient of our cost function at each layer of the network, we can use an optimization algorithm to make changes to the weights and biases. We perform the backpropagation algorithm for each example in our training data. The more examples we show the network, the more it “learns” details and the better it performs on unseen examples. This is how we train a neural network to learn a function that maps inputs to outputs. Once a network is trained, it can be expected to make good predictions on new, unseen examples.

When and why should we use neural networks?

In the most general sense, neural networks can be used the task of prediction. They can process an image of an animal and predict its species, or they can predict a person’s probability of defaulting on a loan, or even predict the translation of a word from one language to another. Some of the reasons why neural networks are so popular is that:

A neural network with a single hidden layer can approximate any nonlinear function. If the relationship between an input and output is very, very complex, a neural network can approximate it.

Neural networks can take multiple types of input, such as images and text, with ease - so long as they can be represented mathematically

Because of the backpropagation algorithm, we can train very large neural networks quickly. This makes them ideal when working with very large datasets

However, it is important to note that not every prediction task requires a neural network!

If the relationship between the input and output is relatively simple - for example, if it known to be linear or quadratic - then there is no need to use a neural network to model the relationship. A statistical model would suffice. Furthermore, if the data you are working with is not very large, there is likely no computational advantage to using a neural network. Finally, and most importantly, if your task requires understanding the relationship between the input and output, a statistical model is the better choice. Neural networks have shown to be excellent at predicting, but they do not reveal any interpretation or understanding about the relationship between input and output. Rather, they simply estimate the function that maps input to output.

Statistical models such as linear or logistic regression, on the other hand, provide an elegant interpretation. Ultimately, given the widespread use and popularity, it is important to know what a neural network is, and how it works. But it is just as important to know the scenarios when it is, or is not, a good idea to use one.

At this point, we have seen a very high-level overview of artificial neural networks. Hopefully, it gives a very basic understanding of the main ideas. The following section provides a more detailed understanding using mathematics.

Mathematical Overview

A neural network is a collection of inter-connected nodes, or neurons, arranged in layers. Each neuron processes input and yields output with a simple mathematical operation.

How artificial neurons process information

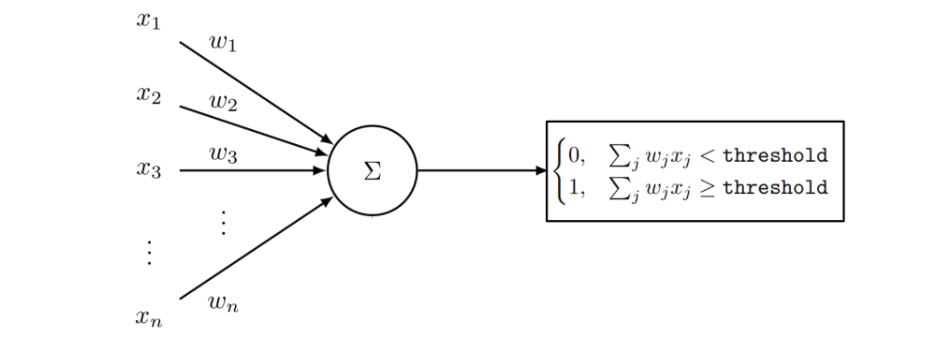

Figure 1: diagram of a perceptron, or a single neuron.

Let $x_1 \dots x_n$ be the input into one neuron, as displayed in Figure 1 above. A neuron performs a weighted sum of the input. This parallels a way of making a decision: take in all the available information and weight it by importance. Let the weights be, for now, $w_1 \dots w_n$, where $w_j$ corresponds to $x_j$. After weighing and summing the evidence, the neuron compares it to a threshold. If the weighted evidence is at least as large as the threshold, the decision is 1 (yes). Otherwise, it is 0 (no). The output of this neuron will be:

$$ \tag{1} \texttt{output} = \begin{cases} 0, & \sum_{j} w_jx_j < \texttt{threshold} \\ 1, & \sum_{j} w_jx_j \ge \texttt{threshold} \end{cases} $$

This single neuron is often called a perceptron, and its decision-making method the ``perceptron rule".

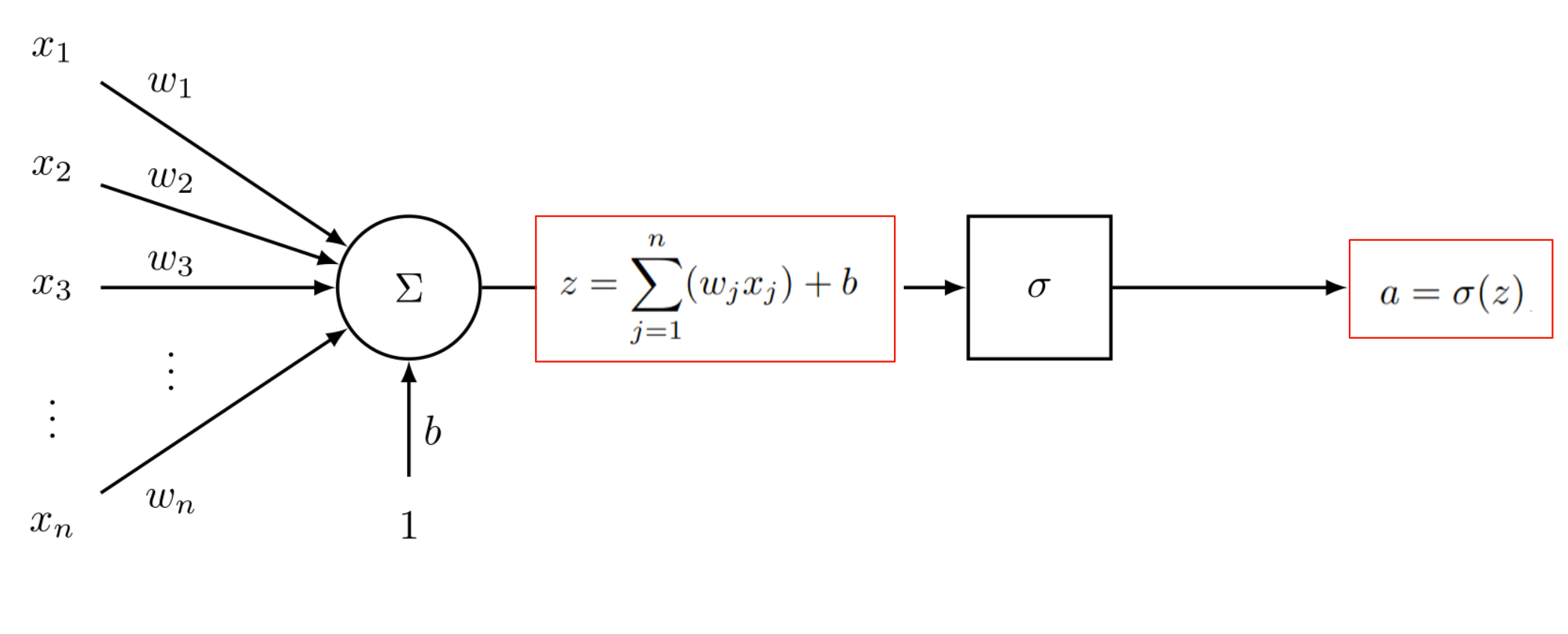

We can re-write the perceptron rule in a more general method by defining some terms. A neuron’s threshold can be looked at as a measure of by how much it shifts its decision. We denote the bias of neuron, $b$, to be $-1*\texttt{threshold}$.

Let us call this weighted sum of inputs added to the bias our $z$ term, or

$$z = \sum_{j=1}^n(w_jx_j) + b,$$

and we can rewrite our perceptron rule as:

$$ \tag{2} \begin{equation} \texttt{output} = \begin{cases} 0, & \sum_{j} w_jx_j + b < 0 \\ 1, & \sum_{j} w_jx_j + b \ge 0 \end{cases} \end{equation} $$

Another adjustment we can consider is the output of a neuron - how it transforms $z$ into a decision. If the neuron outputs either 0 or 1, then this output can shift quite drastically with a small change in a single weight or the bias term. In a network consisting of multiple interconnected neurons, this behavior would be too unstable to allow for learning. So, when building a neural network, we typically want an output to be a smooth function of $z$ that yields a value between 0 and 1. This function, which is typically chosen to belong to the sigmoid family of functions, does not change drastically with a small change in input. Applying a sigmoid activation function, which we denote as $\sigma(\cdot)$ to the output of a neuron will make the neuron, and a neural network, more stable. This form of output is referred to by the literature as an activation of a neuron.

We can re-write the decision-making equation of a neuron as follows:

$$ \tag{3} \begin{equation} a = \sigma(z), \end{equation} $$

where $a$ is the output, or activation, of the neuron. The modified neuron, sometimes called a sigmoid neuron, depicted below:

How a neural network makes a prediction

Returning to Figure 1, we can now give a more detailed explanation of a neural network. In the first layer, the input layer, inputs are represented mathematically. In the first “hidden layer”, each neuron performs the operation described in Equation 2. We will number each layer $l$ as $1 \dots L$, where layer $1$ is the first hidden layer, and layer $L$ is the output layer. The activations of all the neurons in a layer are denoted as $a^{l}$.

Starting with the first hidden layer, the activation of layer 1, $a^{1}$, become the input of the neurons in layer 2. The activations of layer 2 become the input to layer 3, and so on. In more detail, let:

$a^{l}_j$ be the activation of neuron $j$ in layer $l$, and $a^{l}$ is the vector of activations in layer $l$

$w^{l}_{jk}$ be the weight that connects neuron $k$ in layer $l$ to neuron $j$ in layer $l-1$, and $w^{l}$ is the vector of weights that connect neurons in layer $l$ to neurons in layer $l-1$ 1,

$b^{l}_{j}$ be the bias of layer $l$ for neuron $j$, and $b^{l}$ is the vector of biases in layer $L$

The relationship between $a^{l}_j$, the activation of neuron $j$ in layer $l$, and the activations of the previous layer, is:

$$ \tag{4} u = w^{l}_{jk} \\ a^{l}_j= \sigma \bigg(\sum_k^{} u a^{l-1}_k + b^{l}_j\bigg) $$

In words, the activation of neuron $j$ in layer $l$ is the sigmoid of the weighted sum of the activations of the previous layer.

Starting with the input, we compute the activations of each hidden layer, until we reach the output layer, layer $L$. At this layer, the activations are converted into the network’s final output. Consider the example of determining whether an image of an animal is a cat.

We can make an output layer of our neural network have a single neuron. If its activation is above a threshold, the final answer is “yes.” Suppose we want to answer instead the question, “is the image a cat, a dog or a giraffe?” Then, the final layer could have three neurons2. Each neuron corresponds to a species. The neuron with the highest activation becomes the decision of the network.

This is called “forward propagation”. A signal, or input, is moved forward through the network.

How do we train a neural network?

We have now shown how a neural network reads in a signal, or input, processes it, and outputs a prediction. The purpose of a neural network is for it to make accurate predictions for unseen examples. To do that, we present the neural network with training data. Specifically, these are a collection of examples $(x,y)$ where $x$ is the input, such as an image, and $y$ is the label, such as the name of the animal depicted by the image. The neural network can be seen as a model that approximates $f(x)$, or the function that maps inputs $x$ to their labels, $y$. To get our neural network as close to $f(x)$ as possible, we define a cost function, $C$, which measures the difference between the network’s output and the desired output, $f(x)$. A typical example of a cost function3 is the mean squared error, or:

$$ \tag{5} \begin{equation} C(w, b, x, y) = \frac{1}{2n}\sum_{j=1}^n\big(y_j - a^{L}_{j}\big)^2 \end{equation} $$

Here, $C$ depends on four things: $w$ and $b$, the weights and biases in the network, $x$, the inputs, and $y$, the desired outputs. The cost function measures the squared difference between the desired output, $y_j$ and the output of the network, which are the activations of the final layer, $a_j^L$. This notation of the cost function might differ from others; this one is written as an average of the mean squared error cost function for single examples $x_j$.

Naturally, we want to make $C$, the difference between the desired and actual outcome, as small as possible. To do so, we can use standard optimization techniques to find the minimizer of the cost function. However, for a neural network, it is not a simple task. The minimizer of $C$ would be the set of weights and biases that make $C$ as small as possible. This requires that we determine how $C$ changes when we change $b$ or $w$ - in other words, $\nabla_{b}C$ and $\nabla_{w}C$.

Looking at equation 4, we have already established how a single activation $a^{l}_j$ relates to the activations of the previous layer. Plugging in equation \ref{eqn:alj} to $a^{L}_j$, the cost function becomes:

![Figure 1: A scatterplot of Pearson’s father-son pairs, obtained from [3].](../../nnets/eqn-6-2.png)

We can repeat the substitution for the activations for each layer: $a^{L-1}_k, \dots, a^{2}_k$ to get the cost function in terms of all of the weights and biases in the neural network. Needless to say, it is not a simple task to analytically derive the gradient of $C$ with respect to $w$ and $b$.

Backpropagation

Having described backpropogation with words in the first part of the article, we will begin here with the four equations of backpropagation. Some notation: we denote $\delta$ to be the error term of a layer. We also use he Hadamard product, $\odot$, which is element-wise multiplication for vectors. For example, $ \begin{pmatrix} 3\\ 4\\ \end{pmatrix} \odot \begin{pmatrix} 5\\ 2\\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 15\\ 8\\ \end{pmatrix}. $

The first equation relates the error of the output layer, $\delta_L$, to what is input into the final layer: $$ \begin{equation} \tag{B1} \delta^{L} = \nabla_a C \odot \sigma’(z^L) \end{equation} $$ (B1) states that the error of the output layer, $\delta_L$, is the gradient of the cost function with respect to the activations of the output layer, multiplied elementwise with the rate of change of $z^L$, the weighted input into the neurons of the final layer $L$. This relates the error of the final layer to what is input into the final layer, or $z^{L} = w^{L}a^{L-1} + b^{L}$ (recall that $\sigma(z^{L}) = a^L$).

Next, $$ \begin{equation} \tag{B2} \delta^{l} = ((w^{l+1})^{T} \delta^{l+1}) \odot \sigma’(z^l) \end{equation} $$ (B2) relates the error of a layer $\delta^l$ to the error of the next layer, $\delta^l+1$. Since we move backwards, we already know $\delta^{l+1}$. We apply the transpose of the weight matrix $(w^{l+1})$, since we are moving backwards through the network. This gives us a notion of error of the output from layer $l$. We then multiply it element-wise by $\sigma’(z^l)$, which gives us the error in the weighted input to level $l$.

We can use (B1) and (B2) to get the error term of each \textit{layer}. Now, we want to compute the error in terms of the weights and biases of each layer. For this, we can use the next two equations: $$ \begin{equation} \tag{B3} \frac{\partial C}{\partial b^{l}_j} = \delta^{l}_j \end{equation} $$ $$ \begin{equation} \tag{B4} \frac{\partial C}{\partial w^{l}_jk} = a^{l-1}_j\delta^{l}_j \end{equation} $$

Equations (B3) and (B4) relate $\delta^{l}_{j}$, the error term of neuron $j$ in layer $l$, to the rate of change of the cost function with respect to the associated bias term (B3) and weight (B4). With these equations, we have a way to determine by how much to change the biases and weights of the network in order to reduce the error of the cost function.

So, with these equations defined, we can now present a more detailed version of the Backpropagation Algorithm:

- Input: training sample into the input layer, obtaining the activation of the first layer, $a^1$

- Feed forward: For the next levels $l = 2, 3, \dots, L$, compute the weighted sums $z^{l} = w^{l}a^{l-1} + b^{l}$ and the activations $a^l = \sigma(z^l)$

- Compute the error of the network: compute $\delta^{L} = \nabla_a C \odot \sigma’(z^L)$

- Backpropogate the error: Starting with $L$, for each $l \text{ in } L, L-1, L-2, \dots, 2$, compute \ $\delta^{l} = ((w^{l+1})^{T}\delta^{l+1}) \odot \sigma’(z^l)$

- Output: Using (B3), $\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^{l}_j} = \delta^{l}_j$ and (B4) $ \frac{\partial C}{\partial w^{l}_jk} = a^{l-1}_j\delta^{l}_j$, we obtain the gradient of the cost function

To decide how to change the weights and biases, we can combine backpropagation with a gradient-descent learning step:

Algorithm: Training a neural network

- Begin with a set of training examples $X$. %Input $X = x_1, x_2, \dots$, a set of training inputs

- For each example $x \in X$, set the corresponding activation $a^{x,1}$. Here, the notation $a^{x,1}$ is the activation associated with input $x$ in layer $l$. Perform:

(a) Feedforward: for layers $l = 2, 3, \dots, L$ compute $z^{x,l}$ and $a^{x,l}$

(b) Compute the error of the network: $\delta^{x,L} = \nabla_a C \odot \sigma’(z^x,L)$

(c) Backpropogate the error: Starting with layer $L$ and moving backwards, compute $\delta^{x,l} = ((w^{l+1})^{T}\delta^{x,l+1}) \odot \sigma’(z^x,l)$ - Gradient Descent: Starting with layer $L$,

(a) update the weights according to the gradient descent rule and (B4): $w^{l} \rightarrow w^{l} - \eta \sum_{x} \delta^{x,l}(a^{x,l-1})^T$, where $\eta$ is the learning rate.

(b) update the biases according to the gradient descent rule and (B3): $b^{l} \rightarrow b^{l} - \eta \sum_{x} \delta^{x,l}$, where $\eta$ is the learning rate.

While the notation is a bit confusing when looking at a network in the forward direction, it’s handy for looking in the backwards direction. ↩︎

It does not need to have three neurons - it can have instead two neurons, which can encode up to four final decisions. ↩︎

Typical neural network cost functions: https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/154879/a-list-of-cost-functions-used-in-neural-networks-alongside-applications ↩︎